An Historic Heritage

Surrounded by the greatest art and architecture in history, in a country where the Renaissance seemed to happen last week, heritage is not merely something Italians are aware of, it’s the cornerstone of their identity.

Surrounded by the greatest art and architecture in history, in a country where the Renaissance seemed to happen last week, heritage is not merely something Italians are aware of, it’s the cornerstone of their identity.

And for Italian migrants beginning a new chapter in Australia, holding tight to that heritage has helped them forge friendships and close-knit communities. Given that people of Italian descent now make up 4.6% of the nation’s population, it’s also transformed their adopted home.

“Culture involves a whole way of life,” says Sara Wills, Associate Professor in Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne. “It’s not only tangible objects like art or buildings, it’s also social behaviours like dances, sports, habits and customs.”

Heritage, on the other hand, is the distillation of culture. “It’s those things that are passed down from one generation to the next, that give someone a sense of belonging,” says her colleague John Hajek, Professor of Italian Studies.

For migrants, largely bereft of their material culture, heritage can be vitally important. “Identity, mindset, and family influences are some of the strongest aspects of Italian heritage,” says Wills. “These have led to a greater appreciation of Italian culture, which has had a remarkable effect on Australia’s.”

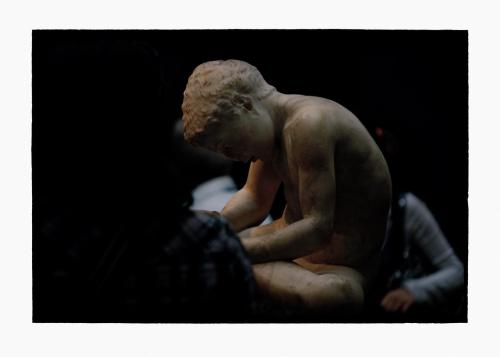

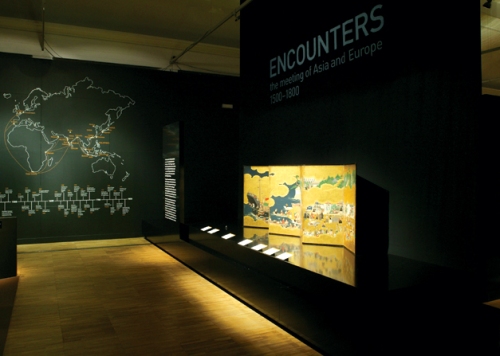

There’s no question that Italy has, for centuries, been a cultural superpower: in fact, it is so highly regarded that 51 cultural landmarks are protected as global heritage, important to all of humanity. Even today all roads lead to Italy, with the Venice Biennale the epicentre of the contemporary art world. But more than that, the country’s art is welded to the very idea of civility.

Dr Ted Gott, Senior Curator International Art at the National Gallery of Victoria, explains, “The genius of the renaissance was that it drew a straight line from Ancient Rome to Quattrocento Italy.

“Wealthy patrons and churchmen saturated Italian cities with art, not only to boast of their power, but to edify the public and instruct them in virtue and civic pride. And that art was read with complete understanding, even by illiterate audiences.”

But in the 18thcentury, English aristocrats plundered this heroic heritage for themselves, taking ‘souvenirs’ as they made their customary travels around Italy. “Huge amounts of Italian artworks were taken back to England, as trophies fit for cultured gentlemen,” rues Gott. And as Britannia came to rule the waves, Italian art became synonymous with English civilisation.

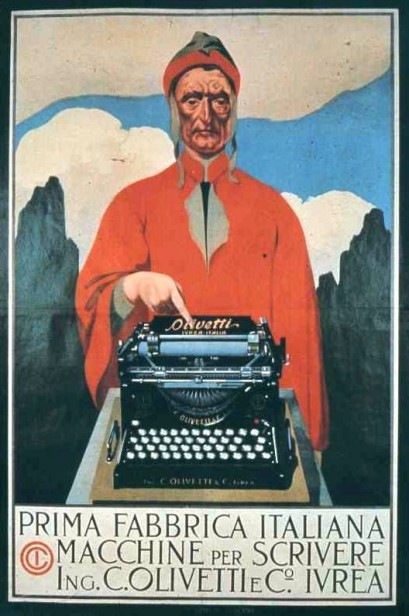

This British Italophilia was imported wholesale to Australia, and in the years preceding Federation, our fledgling art institutions were mandated to collect Italian art as a way to to ‘improve culture’ in the Antipodes.

“Australians at the time were familiar with Italian music and opera, and certainly the old masters,” Gott says. The public certainly responded enthusiastically to the newly-acquired art, from haughty Bronzino portraits to Canaletto’s Venetian scenes, drenched in light.

And they flocked to see the crown jewel: Tiepolo’s magnificent Banquet of Cleopatra– which the Australian government had wanted so much that in 1932, it bought the piece clandestinely from Soviet agents on the steps of London’s National Gallery, paying for it with a suitcase full of cash.

Gott feels that the appeal, like so many Italian works, is that though grand in scale, “it touches the human moment, and makes you part of the story.”

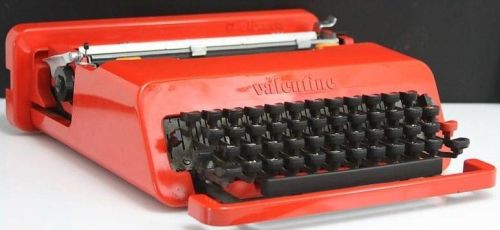

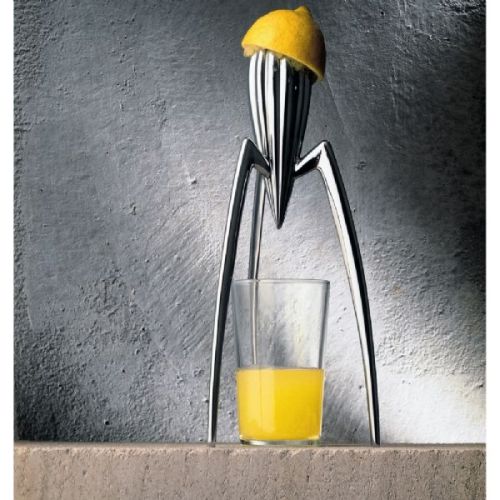

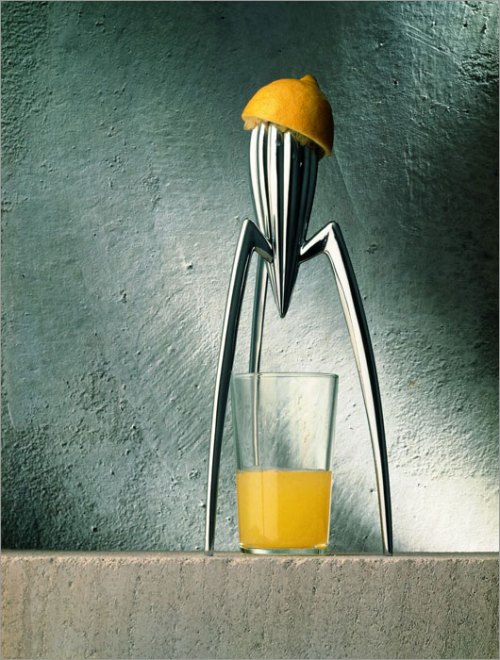

Of course, along with fine art Italy is renowned for bespoke and luxury goods, the product of centuries-old artisanal practices. For Italians, their allure of these wares is entwined with the history and traditions of Italy itself- and they make some subtle statements about the buyer.

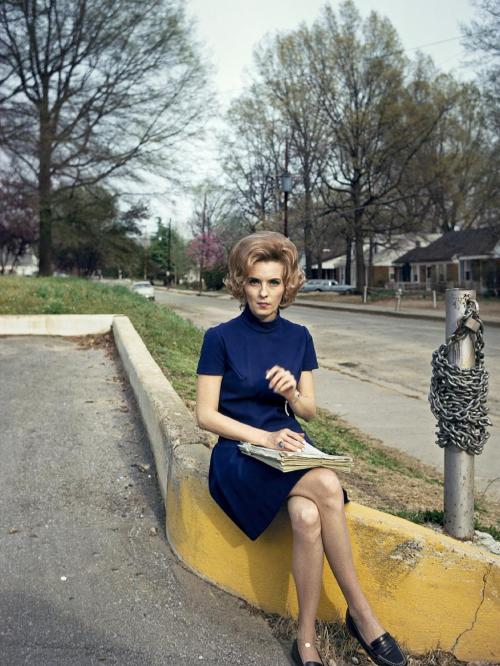

Bespoke tailor Carl Sciarra uniquely upholds this legacy, uniquely offering his customers the exquisite craftsmanship and authentic experience of an Italian sartoria.

“In Italy, it was customary for a a tailor to personally interact with his customers, and develop an intimate understanding of their needs over the years,” says Sciarra. “Tailors developed distinctive regional styles, and created clothes suited to the local climate and the way of life.”

Sciarra seamlessly updates this tradition for the Australian mindset, with garments that are lighter and less structured. “A more relaxed fit is a given,” he says, “with details like a slightly rippled sleeve head, styled pocket details and subtle asymmetries that animate a jacket.”

A different look to built-up, Savile Row-style tailoring, Sciarra’s suits are complex and nuanced, designed for the Australian climate.

He sources his fabrics from Italy and the UK, drawing inspiration from the local and Italian landscapes but toning it down for Australian tastes- the idea is always easy sophistication. “It’s about extracting the character of Italian style, and doing it in a cleaner, up to date way for Australian modes.”

This attitude is itself a venerable piece of Italian heritage, known as sprezzatura, coined by renaissance courtier Baldassar Castiglione in 1528. “Sprezzatura is presenting oneself impeccably, carefully, but in a way that seems effortless,” Sciarra explains. “Italian craftsmanship is about creating and expressing that feeling. “

Many would argue- with good reason- that Italy’s greatest influence has been not on the way Australians dress, but on the way we eat.“Italians live in a romance with food,” says food historian Dr Tania Cammarano. “It’s how we share our love for others, it’s how we mark our moments; it defines what it means to enjoy life.”

Italian foodstuffs were available in Australia a surprisingly long time- pasta, then known as macaroni, was first imported in 1823. But it wasn’t until the 1930s that a handful of Italian restaurants appeared in Melbourne. Dubbed ‘the Spaghetti Mafia’, these close-knit families that ran these eateries shared a love of food and wine, and introduced to the mainly Anglo-Celtic population an exciting new way of eating and living.

While the earliest book of Italian recipes, the First Australian Continental Cookery Book, was published in 1937, it took the great Margaret Fulton to teach Australians how to eat pasta. In addition to a foolproof recipe for spaghetti and meatballs, her classic 1968 cookbook featured a step-by-step guide to correctly eating it, complete with photographs.

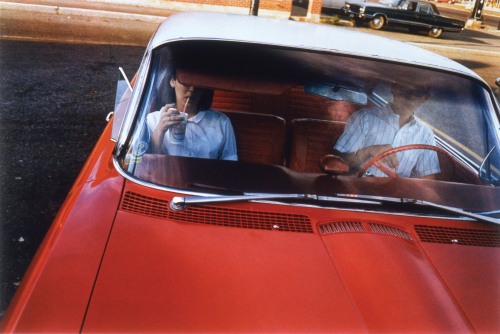

“In the 1960s, Italy was seen worldwide as the source of glamour and excitement,” says Cammarano, “Anything Italian was ‘in’. Food naturally capitalised on the la Dolce Vita craze, and the desirability of being Italian.”

Illustrating her point is a glorious page from a 1960 issue of the Australian Women’s Weekly, in which a stylish couple sips espresso in an advertisement for Max Factor’s Café Espresso Lipcolors, that promised ‘real coffee aroma’ in every lipstick. This was a remarkable leap, considering Australia’s first mainstream café had only opened six years earlier.

“But cooking is not only aspirational, it’s family,” Cammarano says. “It’s a vitally important part of Italian culture to cook and eat together. On one level sharing food creates a family bond, but it’s also a chance to perform our culture and ethnicity- and pass along family recipes and traditions. Every family will have their own way of cooking something, which is how their beloved nonna did it, and their nonna before them.”

Cammarano is fascinated that Anglo-Celtic families are embracing such comfort cooking, taking their cue from the Italians. “This hunger for tradition, for authenticity, is a new thing in Australian food,” she muses. “It’s less glamourous and more akin to peasant cooking, but it’s closely linked to ideas of forming genuine connections with family and personal stories, as an anodyne to what’s become a very disconnected society.’

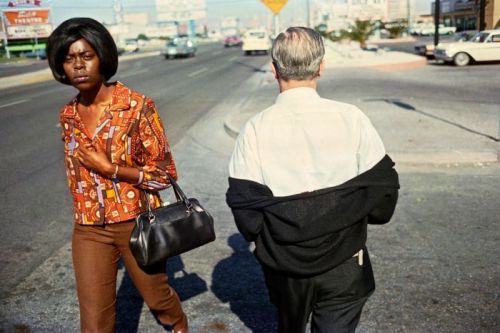

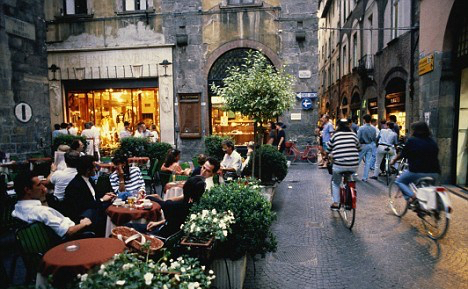

Immigration expert Daniela Grando argues that the intangible aspects of Italian heritage- the convivial community and appreciation of the good life- have influenced modern Australia even more than the country’s cuisine.

“Postwar émigrés were under enormous pressure to assimilate,” she says, “but instead they held on tightly to familiar customs and their regional identity, and established ‘Italian clubs’ to support each other.”

Today, Italian-Australians are proud of their Italianità (Italian spirit) and maintain strong ties to family in both countries. Customs from the old country, like passata day, and the lesser-known salami day, have found a new home in Aussie backyards. While they may be becoming less common in Italy, Grando notes the tradition is stronger than ever here, with family members, neighbours and friends of all ages coming together to cook astonishing quantities of tomato sauce. “The really interesting thing,” she says, “is that it’s now spreading out to non-Italian community groups.”

Equally strong is the Italian habit of treating their public spaces as social spaces- palace to meet, eat, and soak up the sun. “Italians did invent al fresco,” Grando laughs. In Italy, she explains, the whole town turns out for la passeggiata, the evening stroll, an opportunity to see and be seen. “No one just pops out casually. You put on the nice shoes, you make la passeggiata, consider this restaurant or that, sip an espresso, catch up on a little gossip.”

Having travelled widely and been exposed to Italian culture, Australians are embracing what Grando describes as ‘cosmo-multiculturalism’- eager to indulge in the enjoyable aspects of Italian-ness. It’s impossible to imagine Australian cities without their Italian communities, and from eating out to shopping, cooking and catching up over coffee, there’s barely an aspect of day-to-day life that hasn’t been influenced by Italian ways.

As Grando puts it, “Being Australian these days is a lot like being Italian.”

Published Il Tridente, Spring 2019.

In 1962, Bulgari led an exhibition of jewellers in Paris to mark the founding of the Italian Institute of Culture. Where Paris has previously reigned supreme, Bulgari was determined to inject new life into jewellery design, most obviously with its signature style of bold statement jewels that let creativity and colour take centre stage.

In 1962, Bulgari led an exhibition of jewellers in Paris to mark the founding of the Italian Institute of Culture. Where Paris has previously reigned supreme, Bulgari was determined to inject new life into jewellery design, most obviously with its signature style of bold statement jewels that let creativity and colour take centre stage.