More Than a Moment

Photography has long been perceived as the quintessential scientific tool, to record and document with absolute veracity. But almost from the moment of its invention, photographers have sought to push the medium’s creative limits- and in their day, photography’s pioneers such as Hippolyte Bayard, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Alfred Steiglitz, were regarded first and foremost as artists.

Almost 180 years later, in a world where 1.8 billion digital photographs are taken every day, fine art photography is commanding ever-greater attention from art institutions and the viewing public alike. And with good reason, as it continues to grow in depth and complexity, far from simply documenting moments in time.

‘As with any art, photography is driven by its conceptual basis, the ideas it conveys, the thoughts and emotional response it prompts,’ says Susan van Wyk, Senior Curator Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria. ‘There are many ways to engage with contemporary photography, but a work that is well considered, layered and nuanced, always rewards time spent with it.

And today’s audiences are clearly prepared to spend time with it, with contemporary photography having grown to be currently one of the most popular forms of art.

This year, the Head On Photo Festival, Australia’s only annual such event, exhibited work by 800 artists across 100 venues, while Melbourne’s NGV hosts a Festival of Photography featuring such luminaries as Bill Henson and William Eggleston. And later this year, the Art Gallery of NSW will show the surrealist work of Australian Pat Brassington, as well as a major survey of the late Robert Mapplethorpe from LA’s Museum of Art and J Paul Getty Museum. Australian art museums’ own holdings of photography now rival traditional media, and their mission to showcase local photographic artists to the world culminated in the selection of Tracey Moffat to represent Australia at this year’s Venice Biennale.

But this has not always been the case; the idea of photography as fine art lagged in the Australian imagination. When the Centre for Contemporary Photography was established in Melbourne in 1986, photography was largely regarded either as documentation- enshrined in magazines like Time, Life or National Geographic– or as advertising, with little in between. And while there was plenty of photographic art produced, the market was almost non-existent, and exhibiting institutions had scarcely begun to build their collections.

‘Photography needed a different kind of space,’ says CCP Director Naomi Cass, speaking both figuratively and literally. ‘It needed a particular space to show, and for specific criticism, a space to put a new framework around photography and contextualise it as art alongside more traditional media.’

The Centre’s strategy of exhibition rather than collection not only liberated photography from the marketplace, it also gave it vital room to grow and experiment. At the same time, it brought a great deal of exposure for emerging photographers as artists. Its salon-style events drew regular visitors and quickly demonstrated that fine art photography could be accessible and enjoyable, as well as aesthetic and considered.

But even more, that accessibility created an artistically literate audience who simply ‘get it’, and are able to connect with the various avenues contemporary photography explores, and the photographers who are re-imagining our world in unpredictable and unconstrained ways.

‘That imaginative enquiry is what has marked photography as art from its very beginning,’ says NGV’s Susan van Wyk. ‘Artists continually re-frame what they see, and experiment with different development processes to imbue a photograph with emotion and imagination.’

This is nowhere better evident than in the NGV’s exhibition of William Eggleston’s Portraits, part of the Gallery’s Festival of Photography. Photographed in the American South in the 1960s, Eggleston’s images depict friends, family and strangers encountered in passing by his lens. Although using snapshots similar to the vernacular photography of the day, Eggleston’s works are remarkably sophisticated in composition, drawing attention to the closeness between strangers, and the distance between friends.

‘It’s not as straightforward as simply diarising,’ says van Wyk, ‘but neither are they treated with any sentimentality. Eggleston wants his audience to get beneath outward appearances’.

Eggleston’s saturated, practically vibrating colours- as van Wyk notes, unheard of among serious art photographers of the time- deftly grabs and guides our attention. The rich orange blouse of an African woman and a man in stark black and white passing in the street (Untitled, 1965-1969) is as composed as a sonnet; two teens sipping soda in a blazing red Buick (Untitled (Couple in Red Car in Drive-In Restaurant) 1965-68) is like a breathless still from a Hitchcock film, shimmering in the Memphis heat. One of his most striking portraits (Untitled (Memphis Tennessee) 1969-71) is of a carefully coiffed woman incongruously and ominously sitting on a curb: her dark blue cocktail dress speaks of prim composure: but it is the yellow-painted curb that focuses attention on her tightly crossed legs, and connects her to the padlocked bollard wrapped in chains beside her.

But while there is almost a sense of voyeurism to his shots, each moment trapped in amber reveals beauty in the banal, and poses layers of questions of identity, relationships, memory and perception.

‘Eggleston’s impact on impact on photography since the 70s has been enormous’ says van Wyk, and notes his lasting influence on current filmmakers such as David Lynch and Sofia Coppola.

The NGV’s Festival of Photography showcases an enormous diversity of photographic work comprising digital media, documentary found photography, and of course a star turn by Bill Henson. Like Eggleston, Henson’s work is imbued with emotion and authority, but uses the language and aesthetic if renaissance art in luminous works of uncompromising, affecting beauty, that draw us ever deeper into the image.

Art history is one of the multiple histories photography has to draw on, so it’s important to show the many ways we encounter it,’ says van Wyk.

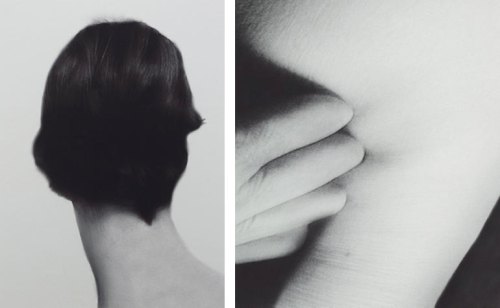

The same could be said for the work of Pat Brassington, whose exhibition opens at the AGNSW this August. One of Australia’s leading photographers, Brassington has long been inspired by surrealism, psychoanalysis and the uncanny in her treatment of the body as a malleable landscape. Her work draws strongly from the unconscious, taking the viewer into a world that is familiar, yet altered and shifted to create alternate realities.

In October, the AGNSW will also host a survey exhibition of Robert Mapplethorpe, the American photographer regarded as the single most influential of the 20th century.

Isobel Parker Philip, Acting Curator of Photography at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, believes that Mapplethorpe, although known for his eye for detail, is more properly read in terms of his overall artistic vision.

‘He is not about documenting the curve of a flower stem or human figure, he is about the relentless pursuit of perfection that that line embodies,’ she explains.

‘It’s our hope that audiences will look at iconic works like these to gain a fuller understanding of Mapplethorpe’s conceptual processes, not just his formidable command of the medium.

‘We want them to look mindfully at the work, not simply through it.’

Parker Philip is excited that the conceptual basis of photographic art is being applied more energetically than ever before, not just to the treatment of its subjects, but to its ever-expanding capabilities.

‘Artists have always manipulated the medium and done unexpected things, but right now artists are really dissecting the inherent nature of the medium, and unhinging what people expect to see,’ she says.

‘Today, audiences live in a sea of photographic imagery, and as a result are extremely visually literate- navigating between commercial, social and fine art photography is just second nature to them. They are already primed to look at photography in a whole new way, and the reciprocal effect that has on artists is considerable, making them interrogate what it means to create a photographic work in the 21st century.

‘In many ways, there’s almost an assumption that a photographic artwork is reducible to its subject- that the image is all that counts, and we can almost bypass the photographic process on the way to the subject.

‘But there’s much more to a photographic work than that- or it might as well not be a photograph. Artists now are experimenting with all but forgotten processes, or inventing new ones to turn the photograph into a sculptural presence, or an evanescent one, one that asserts time or even thwarts the ability read the image.’

Parker Philip has seen these strategies draw a different interaction from the audience in the recent exhibition New Matter- recent forms of photography, making them stop and contemplate a work that’s not easily recognised, or defies fiting into a neat category.

Matthew Brandt’s work is just such, using gum bichromate photography (popular 1890-1920) known for its soft, dreamy tints that could resemble charcoal or watercolour. But Brandt goes further by developing the plate with pigments made from physical elements like dust, to create ghostly traces of the physical world.

Indigenous and Maori artist James Tylor similarly revives antiquated processes including daguerreotype- printed on a silvered plate- to reclaim control of one of the tools of colonisation and cultural disruption. The natural specimens he photographs, severed from the land and scientifically dissected, silently cuts across the narrative of settlement by showing its reality.

Perhaps the most innovative of these experiments are Justine Varga’s images, that not only challenge the idea of the photographic instant, but are produced without even the camera. Varga exposes the negative to light multiple times, and then subjects it to daily wear and tear for up to six months. Although technically an error, the patina of the degraded negative becomes a feature, and a record of time captured.

‘Photography has never been fixed or stable,’ Parker Philip asserts. ‘Photography continually re-evaluates itself, and forces us to be reflexive when viewing- or curating. Experiments like this are at the forefront of an international conversation on photographic art’s history, its place in contemporary art, and where it can go from here.

‘In a world were photography had become so ubiquitous, it’s crucial to keep questioning.’

Published Il Tridente, Winter 2017